Great Composer Pilgrimage Part 1—Haydn-Mozart-Beethoven

Haydn's signature (on the right) on the Deed of Trust for his home near Esterhazy Castle

I’m staring at a Deed of Trust under glass in a spacious home in the city of Eisenstadt, outside of Vienna. At the bottom of the deed is a clear, neatly scripted signature, “Joseph Haydn.” As much as you might know about Haydn, you probably wouldn’t imagine this document exists unless you visited this house. Then you would also discover he needed both his father-in-law and Prince Esterhazy to co-sign his loan. And that it was in this very house, just down the road from Esterhazy Castle, that Haydn composed his first string quartets that defined the most important genre in chamber music. Also in this house, Haydn posted on his walls brief musical settings he made of humorous and virtuous phrases.

I confess an ulterior motive for our 2015 LA Youth Orchestra European Tour was to drag my students along on the trip I always dreamed about—to explore the haunts of the great composers. To my delight, the students shared my excitement as we visited the homes, retreats, and museums of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Dvorak, walking where they walked, seeing some of what they saw. And Europe, both for tourism and genuine pride, is actively preserving many of the great composer locations both as shrines and museums. Unlike the USA, the billboards and posters in Vienna, Prague, and Leipzig continually present notices about concerts of Beethoven, Mozart, and Bach, not today’s mega-pop stars.

So I envisioned a “great composer” pilgrimage first in Vienna and Prague with my orchestra students, and then afterwards privately to Bach’s St. Thomas Church in Leipzig. I joked with friends that I would bring a shovel and dig up some of those cantata pages tragically discarded after Bach’s death. It turned out digging was a major theme. Digging to get a sense of the composers' daily lives was one layer. Digging beneath the incredible light and beauty of European cities to a very dark history was another. World War II was naturally an ever-present shadow. Being overwrought visiting a concentration camp—that you expect. But I found myself suddenly in tears reading a chilling letter in the Mendelssohn House in Leipzig that matter-of-factly explained to Mendelssohn’s grandson why his grandfather’s monument was torn down in 1937. The letter from the Leipzig mayor explained the reasoning: first, Mendelssohn was a Jew and therefore could not possibly represent a German city renowned for its music; second, Leipzig had not erected any monument to Richard Wagner, the “greatest musician and writer of this city.” (Apparently Bach didn’t make the grade either!) Horrifying! The Cold War continued this darkness, with its tentacles going right up to 1989 and, of course, today.

My ultimate goal—to visit St. Thomas Church in Leipzig and "dig" for a lost Bach cantata :)

Plans for our trip didn’t begin high-minded. Our tour company originally suggested sightseeing activities such the locations for the film The Sound of Music, an amusement park, and a chocolate factory. I nixed those and instead proposed Esterhazy Castle in Eisenstadt where Haydn was Kapellmeister, Heiligenstadt outside of Vienna where Beethoven wrote his famous unsent letter describing his heartbreaking onset of deafness, and the Lobkowicz Palace in Prague with its famous manuscript collection (ever notice all the Beethoven works that bear a Lobkowitz dedication?). We had limited time, so of course we missed many important places—Schubert, Brahms, Mahler, and Schoenberg in Vienna, Mozart in Salzburg, etc.

But visiting these different places do make the great composers come alive. They no longer seem of a “distant past.” Quite a few of the buildings in European cities go back to the 12th century. For Mozart, the clock tower in Prague must have seemed as historic as it is for us today.

The famous Astronomical Clock in the Prague town square

Further, the items in the composer homes include possessions and items not so different than those we have in our homes. Bach owned a safe (a chest with 11 locks-more on this later!). Both Mendelssohn and Wagner owned busts of Bach in their studios. Many of these composer tourist sites are becoming something like shrines, undergoing major renovations that make them clean and new. Surprisingly, rather than feeling artificial or inauthentic, you feel closer to the time the composers lived since you don’t have to imagine what things looked like earlier beneath centuries of grime. For example, the interior of Bach’s St. Thomas Church in Leipzig is completely rebuilt, nothing like it was in Bach’s time. Yet sitting in the pews at a service, enjoying the marvelous acoustics (which probably were similar in Bach’s day), singing the chorales, hearing the choir and the new Baroque organ—you feel like you can absolutely imagine how it must have felt as a congregant to hear Bach’s music in the 18th century.

Haydn House, Eisenstadt

Haydn's house in Eisenstadt near Esterhazy Castle

Listing of Haydn's possessions destroyed from a house fire—a velvet robe, dishes, framed pictures, etc.

Back to the Haydn house. While he was living there, he experienced two fires! One destroyed most of what he owned. He inventoried his losses in a document that still exists. It gives a good idea of what he owned and how he furnished his house. Haydn’s patron Nicolas Esterhazy came to his rescue after the fire, paying to rebuild the home—Haydn even took the opportunity to add additional rooms! As you examine the legal documents, letters, and manuscripts at the Haydn house, you see that Haydn was a very meticulous and capable manager. And that sense of humor we love in his music was evident from the postings on his walls.

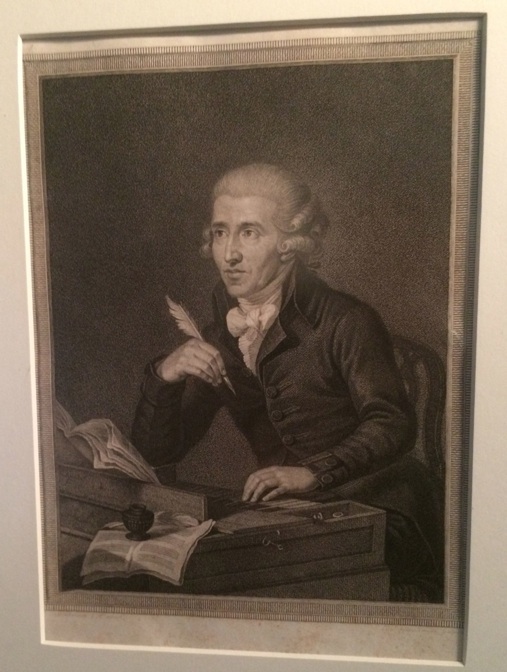

Haydn at the piano by Luigi Schiavonetti, neat and organized, but the ink looks like it might spill :)

Haydn sketch. His manuscript though was beautiful and meticulous—

Here was a discovery—Beethoven copying out Haydn's op. 20 #1 string quartet that was composed in this very house! Not Beethoven's far more wild manuscript.

I always thought it odd reading that among Haydn’s many duties was arranging music for marionette shows. As it happened, my friend Charla knows the owner of the Marionette Theater at Schönbrunn Palace and arranged for a special private show for our orchestra. We were all transfixed as we watched Christine Hierzer-Riedler and her team coax beautifully carved characters to move, act, and dance with virtuoso realism. Fantastical animals—butterflies, horses, even a unicorn!—swept across the magical dark miniature stage. Surely this was the “silent cinema” entertainment of the 18th century, and just as compelling. I now understand why Haydn’s musical arrangements were so important for these Esterhazy entertainments.

Here’s a video (in German) of the Marionettentheater:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xANokkUgJfg&feature=youtu.be

Marionette Theater, Schonnbrünn Castle

Esterhazy Castle

Our first LA Youth Orchestra European concert was at the appropriately named Haydn Hall (Haydnsaal) at Esterhazy Castle. We saw many beautiful halls in Europe, but none more magnificent than this one, the actual chamber where Haydn performed much of his music. It does feel like the Sistine Chapel, with its magnificent ceiling frescos depicting Hungarian history. It was originally a dance hall with marble floors. Legend has it that Haydn convinced Prince Esterhazy to replace the marble floor with wood to improve the acoustics. That, plus the large side windows being deeply recessed creates a full reverberation with no muddiness. I found Haydnsaal to have even better acoustics than the legendary Musikverein in Vienna. Haydn’s Symphony No. 3 sounded clear, even with my full orchestral arrangement. It just fit the hall and as I conducted, I imagined Haydn possibly premiering it in this very room. What incredible fortune he had to have this position! I was reminded of the famous statement he made to his biographer Greisinger: “My prince was always satisfied with my works. Not only did I have the encouragement of constant approval, but as conductor of an orchestra I could make experiments…I was cut off from the world; there was no one to confuse or torment me, and I was forced to become original.”

Esterhazy Castle in Eisenstadt—where Haydn walked to work

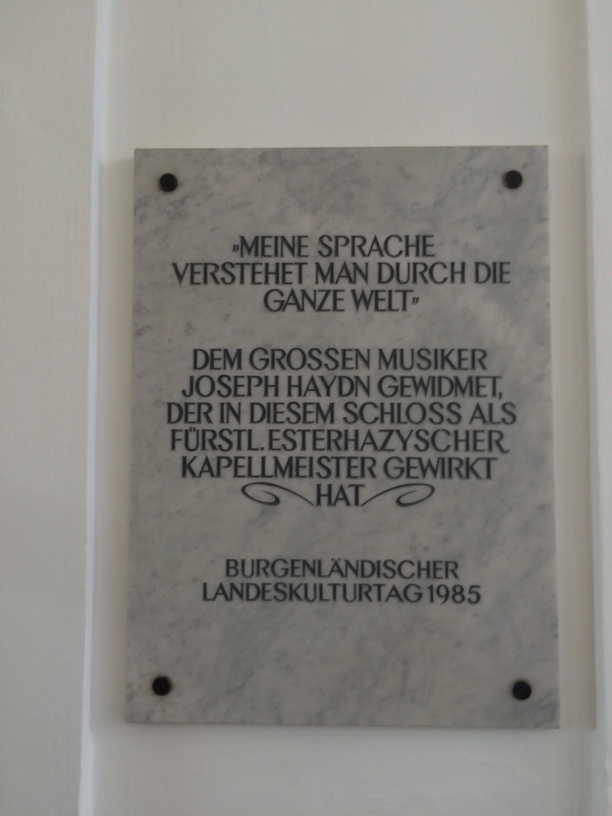

Inscription inside Esterhazy Castle—Haydn's famous quote to Mozart about why he would be fine traveling to England even though he only spoke German—"the language I speak is understood by the whole world"

Haydn Hall in Esterhazy Castle—the reverence of the Sistine Chapel with perfect acoustics!

Mozart House in Vienna

The Mozart House in Vienna is not so helpful for envisioning the composer’s apartment or workspace. This house was indeed where Mozart composed The Marriage of Figaro—the opera—right near St. Stephen’s Cathedral, where he married Constanze (a plaque in the cathedral tells you so!). Unfortunately, no artifacts or original furnishings exist in the apartment, so the entire structure has just become a museum of Mozartiana under glass. We learn that Mozart’s money problems were largely the result of gambling, which at the time was a debt of honor. That meant the money had to be paid back quickly to avoid a duel or imprisonment. That explains the beseeching tone in several of Mozart’s letters desperately asking friends if he can borrow money. There were many autograph facsimiles, but as with most other museums, little analysis or revelations were provided.

Mozart Plaque in St. Stephen's Cathedral—he and Constanze were married here, his memorial with the Requiem was performed here.

St. Stephen's Cathedral interior

Famous St. Stephen's Cathedral tiled roof

Mozart Bertramka House in Prague

This site was even sadder. Mozart finished his opera Don Giovanni as a guest in this home estate, but nothing is left to show of it. The estate was finally returned to the Czech Mozart Society in 2009, but it was empty—stripped of all its furniture and decorations. The story is familiar. It had been a Mozart shrine since the 1830s until the Nazi invasion. Then afterwards, the Communist government confiscated the property and all its manuscripts, moving them to the National Museum. After the fall of the Communists, the Czech Mozart Society applied for restitution, but when it was granted in 2004, the institution formerly curating the estate took everything away! So we walked through empty rooms with a few display cases. Outside, what was once clearly a beautifully landscaped garden was now mostly weeds. We walked up the hill in back and came to a Mozart sculpture that was dedicated in 1876. Beyond that was an unmarked large stone table that the museum curator said was where Mozart wrote some of his opera. Even dilapidated, the surroundings were beautiful and with a view of the city and the chirping of birds, it was not difficult to imagine why Mozart liked staying here. Two of his sons spent many years living at this estate after their father died.

What's left of the Mozart Museum in Betramka, Prague where Mozart composed Don Giovanni

Stone table in the back of Betramka where I was told Mozart composed—now just concrete ruins in a beautiful but weed-strewn hilltop

Proof that Mozart changed his mind sometimes :)

Beethoven at Heiligenstadt

Beethoven lived in dozens of apartments in Vienna, but I wanted the orchestra to visit his retreat about a half hour away in Heiligenstadt. That’s where he wrote the remarkable letter (unsent and discovered only after his death) to his brothers explaining his deafness and exploring a reason to stay alive. He explains the “secret” behind his angriness, moodiness, and seclusion: “Yet I could not bring myself to say to people, ‘Speak up, shout, for I am deaf.’ Alas! How could I possibly refer to the impairing of a sense in me should be more perfectly developed than in other people , a sense which at one time I possessed in the greatest perfection…”

A stream not far from the apartment inspired the “By the Brook” movement from the Pastoral Symphony. As a museum, it is quite the oddity. It has a facsimile of the letter, but the other exhibits are frankly macabre: a lock of hair, the lock plate to his workroom, a door lock to the room he died in (at a completely different location). Nevertheless, you can feel the peaceful quality of the apartment and its surroundings, away from the hubbub of the city. And it provides an important clue to the private interior of Beethoven’s tortured life.

Beethoven apartment in Heiligenstadt

Bizarre relics in the Heiligenstadt museum—a lock of Beethoven's hair and the lock plate from his work study.

The Heiligenstadt Testament, displayed like a school announcement board-- strange

Lobkowicz Palace in Prague

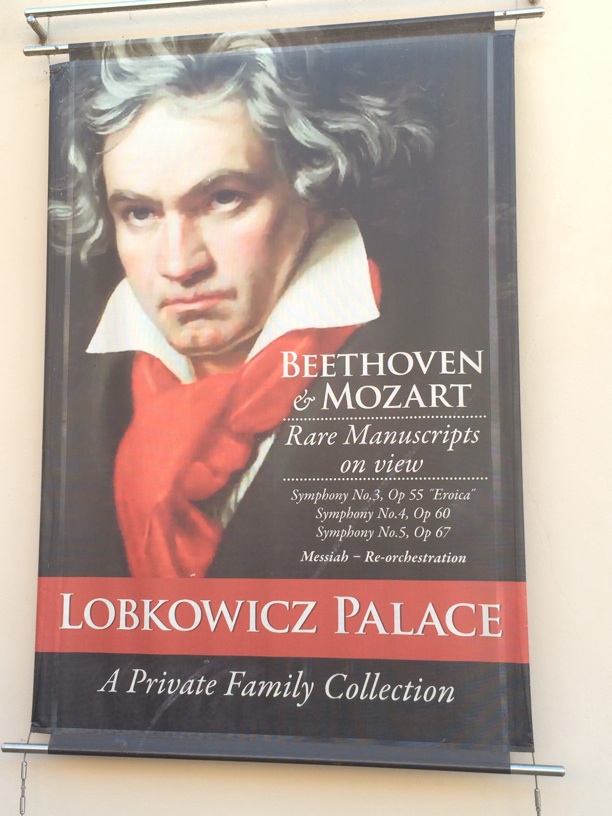

poster in front of Lobkowicz Palace

I looked forward so much to seeing the famous Lobkowicz manuscript collection in Prague. It includes the scores to Beethoven’s 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 7th symphonies. Prince Lobkowicz was Beethoven’s friend and one of his three principal patrons. His descendant Bill Lobkowicz lives in New York today! The Nazis confiscated the collection and in the following Cold War, the communist Czech government kept it as state property and disbursed it to various libraries. Not until 1992, with the Restitution laws in the Czech Republic, was the collection and much of their land and other property restored to the Lobkowicz family!

So close, but so far! The manuscripts on display were just a small part of one small room largely devoted to the Lobkowicz instrument collection. But there, sandwiched between instruments and paintings under glass were the actual orchestral parts Beethoven used for the premiere of his 5th symphony! The cover in the copyist’s hand noted the title and composer, and listed the instruments and parts. A description plate mentioned that Beethoven’s personal markings were in the parts. But the book was closed! It looked obviously fragile with frayed paper edges, but please—Dear Bill Lobkowicz—please devote an entire room to this manuscript and post facsimiles of the pages where Beethoven marked corrections and changes!! This is by far the most interesting object in your entire collection. It deserves a much more through display.

Original orchestra parts for Beethoven's 5th! The descriptive plate said that Beethoven's corrections were in the parts, but only the cover was displayed.

Original first printed edition of Symphony No. 3

The original parts for Beethoven's string quartets op. 18—again, frustratingly closed!

Many other manuscripts and printed editions in the Lobkowicz collection are remarkable. There is the Mozart manuscript score of his arrangement of Handel’s Messiah. Also under glass were the first printed edition of Haydn’s oratorio The Creation and Beethoven’s Eroica symphony. These should all be presented in yet another room with scholarly explanations and analysis. OK, I’m off my soapbox. Onwards to the Romantic composers in Part 2.