Great Composer Pilgrimage Part 2—Dvorak-Wagner-Schumann-Mendelssohn

We, the LA Youth Orchestra, finished our composer journey with the Dvorak Museum in Prague. I then continued on myself to Zürich, Switzerland to visit my friend Charla Hofstetter. Charla is a fine accompanist who was my classmate at UCLA years ago in Elaine Barkin’s two year music theory course. Charla knew my keen interest to visit composer sites. In Switzerland, she took me to two different Wagner homes and a Brahms monument. Then we both traveled to Leipzig to visit Mendelssohn and Schumann’s houses, and, ultimately, the St. Thomas Church and Bach Museum, my shovel for digging up a Bach cantata at the ready…

Dvorak Museum, Prague

Dvorak Museum in Prague

The first thing our tour guide told us about Antonin Dvorak was that for the Czech people, Dvorak is always the second composer. Bedrich Smetana is the first. I gathered from the guide’s introduction that Dvorak was a distant second. :) This is a holdover from both nationalist fervor and recent Communist times. Dvorak, you see, visited the evil imperialists of America to make money. Worse, he composed the New World Symphony. So for many in the Czech Republic, he sold out— he was no patriot. Amazing how you could underplay one of the greatest symphonists and chamber music composers. Meanwhile, Smetana, while certainly a major composer, is not on the order of Dvorak, and much of his music remains unknown to the rest of the world.

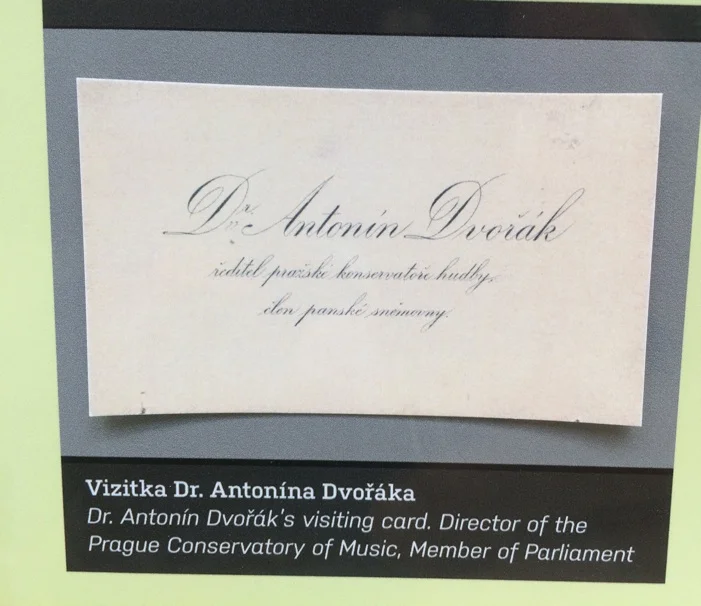

The museum displayed Dvorak’s elegant writing desk, his piano, his viola, his business card (!), and many beautiful manuscripts and letters. It emphasized his vocal music (which we rarely hear) and his trip to America with the “uproar” at his assertion that the future of American music was with the melodies of blacks and Native Americans. No mention of his chamber music, other than that he played viola. How odd. Chamber aficionados adore Dvorak and I’m sure not a day goes by on planet Earth where one of his chamber works is not being played. From this museum, you wouldn’t know he ever had written more than vocal music and symphonies. So is Dvorak viewed with tinges from the Cold War perspective.

Dvorak's writing desk

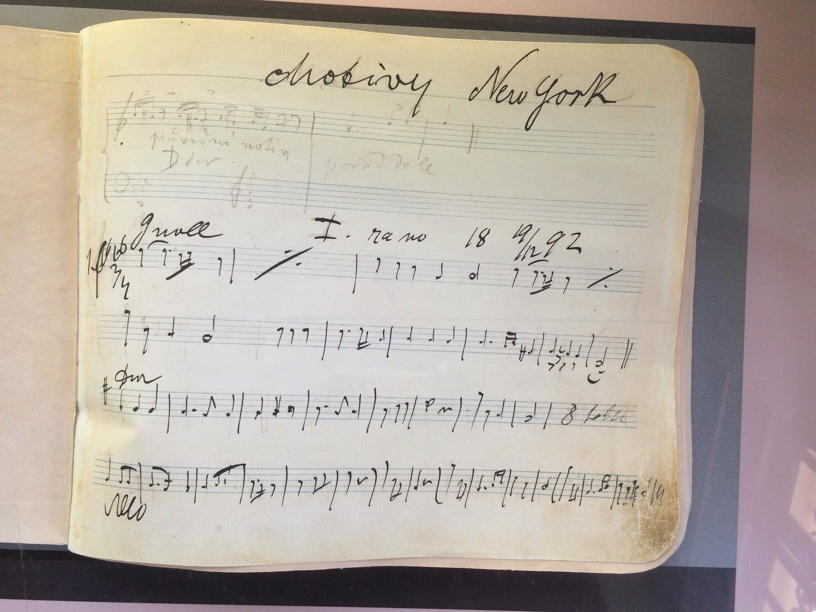

New York sketchbook

Dvorak's business card!

Dvorak's piano

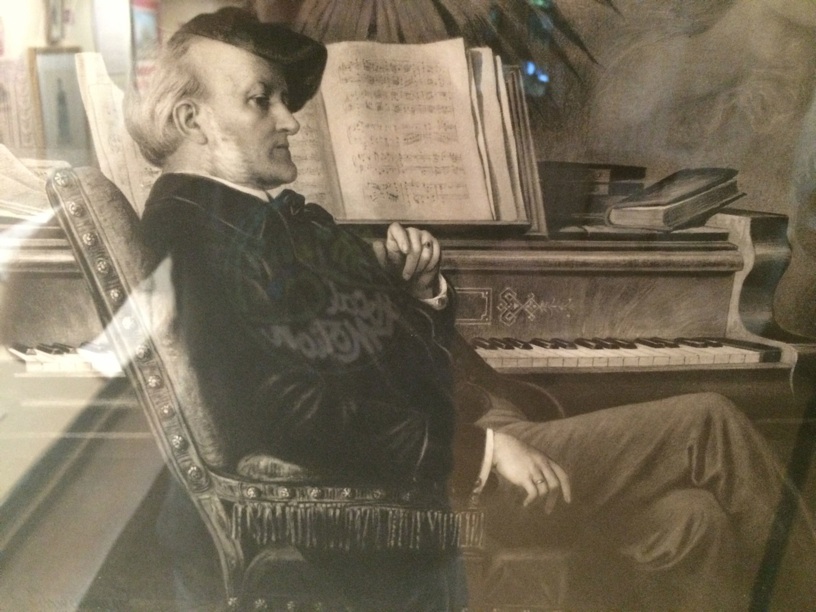

Dvorak in 1896

Letter from Edward Hanslick to Dvorak letting him know that he won a scholarship from Germany and that Brahms was especially impressed with his work. This was to be Dvorak's big break.

Wagner in Switzerland

After Prague, I traveled to Switzerland, a country that has been for composers both a refuge and an inspirational retreat. I never knew Brahms composed his German Requiem in the picturesque town of Thun, Switzerland. But my friend Charla was adamant about finding the monument.. She asked around and sure enough, we found it along the riverbank where he stayed, though the house no longer remains.. Before Brahms, Mendelssohn traveled to Switzerland and painted remarkably beautiful and accurate watercolors of various places. Later when I visited Mendelssohn’s house in Leipzig, I spied his watercolor of Thun, and even before reading the title plate, I immediately recognized the town I had walked through just days before in Switzerland!

Brahms monument in Thun, Switzerland where he composed the German Requiem

But the composer most enshrined in Switzerland is Richard Wagner, this despite the fact he was a native of Leipzig, the town famous for Bach and Mendelssohn! In Zürich at the voluptuous Villa Schönberg, the estate of the Wesendoncks, Wagner composed Tristan und Isolde. You could say this was the very house in which Western harmony was redefined. The rich, unexpected, and never-resolving chord progressions of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde ushered in the Modern era. Also in this house, Wagner composed his Wesendonck Lieder, set to poems of Mathilde Wesendonck, Otto’s wife, with whom Wagner probably had an affair (Wagner was also married at this time).

Villa Schönberg, Richard Wagner's residence in Zürich where he composed Tristan und Isolde.

Tribschen in Lucerne, where Wagner lived with Cosima and composed the Ring Cycle.

The most important Wagner museum/house in Switzerland is Tribschen, the estate in Lucerne where Wagner lived with Cosima, Hans van Bülow’s wife. If you need a brush up on the notorious story, Cosima was Franz Liszt’s daughter. She was married to the great pianist and conductor van Bülow, who Wagner was entrusting to perform his Ring Cycle operas. Under van Bülow’s nose, Wagner and Cosima lived together and had three children, each named after characters in the Ring Cycle. Only with the third child, Siegfried, did Cosima’s husband Hans van Bülow finally throw in the towel and divorce her (he subsequently devoted himself to the music of Brahms!). Wagner and Cosima married in 1872. So this was the home where Wagner composed his famous Siegfried Idyll, the birthday present Cosima woke to when a chamber ensemble premiered it on the stairs of their villa. Tribschen is where Wagner composed much of the Ring Cycle.

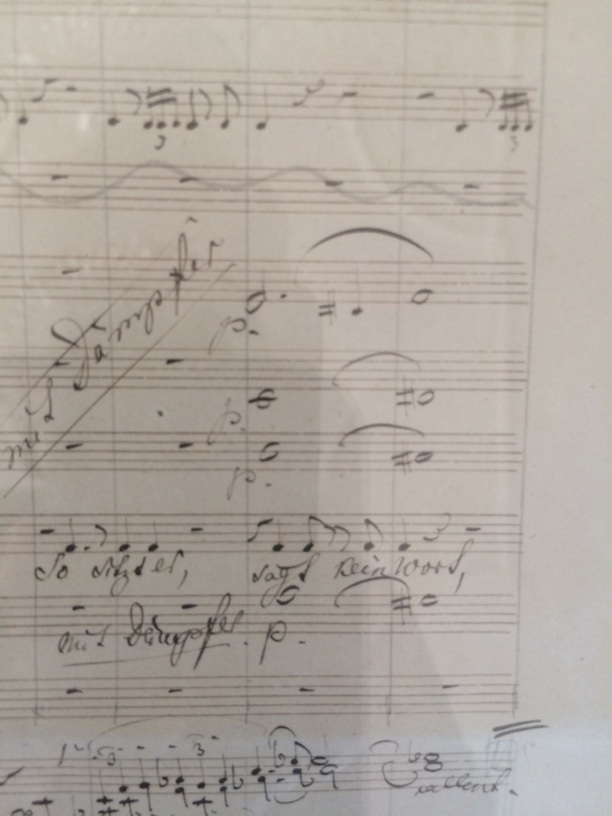

Manuscript page from Wagner's Siegfried Idyll, his birthday present to Cosima right after the birth of their third son Siegfried

This large house with its exquisite view has become a museum with a superb collection of Wagner memorabilia and manuscripts. One amusing and fantastic example is a card of remembrance Wagner created for his Zürich concerts. On the card he beautifully notates his “hit” tunes from The Flying Dutchman, Tannhaüser, and Löhengrin.

Wagner created this remembrance card for his concerts in Zürich featuring his operas with his 3 "hit tunes." For instance, you can read the famous Bridal March from Lohengrin on the third line.

However, most of the exhibits are of music and events that occurred in later years. There is an autograph score of Siegfried Idyll—just stunning manuscript. There are sketches for Die Meistersinger and Die Götterdämmerung. We see his Erard piano, and on the wall framed photographs of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Gluck.

manuscript of a page from Götterdämmerung

Wagner's Erard Piano

In his wedding photograph, we see him standing above and gazing down at an adoring Cosima. That leitmotif continues in an oil painting titled “Wagner at Home,” where he towers above both Cosima and her father, Franz Liszt. We read Cosima’s words about her total devotion to Wagner based on his genius.

Richard and Cosima's wedding photo

Painting of Wagner at home with Cosima and Franz Liszt

The exhibits then move to the Nazi era. Cosima embraced the anti-semitism of the German Nationalists. We see a picture of Cosima’s daughter-in-law Winifred and her son walking with their friend Adolf Hitler.

Scholarly apologists frequently argue that there are nuances to Wagner’s anti-semitism and that his writings had little or no influence on Nazism. I’m not convinced. This museum lays out a man who expected veneration and who dominated everyone around him. His ideas of racial purity were the same ideas the Nazi’s embraced. They are there for anyone to read— and Wagner wrote even more prose than music! In his final years, he continued to write about “the ruin of the white races.” (you can read more beginning with Wagner Controversies, a brief Wikipedia article)

Nevertheless, the primary impression I had visiting Tribschen is the genius and beauty so apparent in Wagner’s music manuscripts. His writing is as rich, inventive, and ever-flowing as the tapestries, furniture, and plush garments he surrounded himself with in this home. He is the only “demi-God” in the pantheon of great composers—regarded so by himself and many of the great minds of his day— and this museum captures that quality, in all its disturbing genius. I highly recommend the visit.

From Switzerland, Charla and I took the train to Leipzig, Germany, specifically to see Bach’s tomb at St. Thomas Church. But Leipzig is also the city where Clara Schumann was born. She and Robert spent their first married years in a house there that is now a museum and school. And of course, Leipzig is where Felix Mendelssohn created the Bach revival, conducted the Gewandhaus Orchestra, and established the Leipzig Music Conservatory.

Schumann house in Leipzig

Plaque on the building where Robert and Clara first lived

Schumann House in Leipzig

Here is the first apartment of the music Romantic Era’s most famous love affair. The whole building is currently a school with the Schumann apartment a small museum within. You know the story. Frederick Wieck, Clara’s father and a highly regarded piano teacher, groomed his daughter for a brilliant concert career. Robert Schumann came to Leipzig to study with Wieck and fell in love with Clara. The rest of the tale is the well known love affair of the Romantic Era. When Wieck finally relented and Robert and Clara got married, they first lived in this apartment where Robert composed his first symphony and many other works. Visitors to the Schumann house included Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Richard Wagner, and Hans-Christian Andersen.

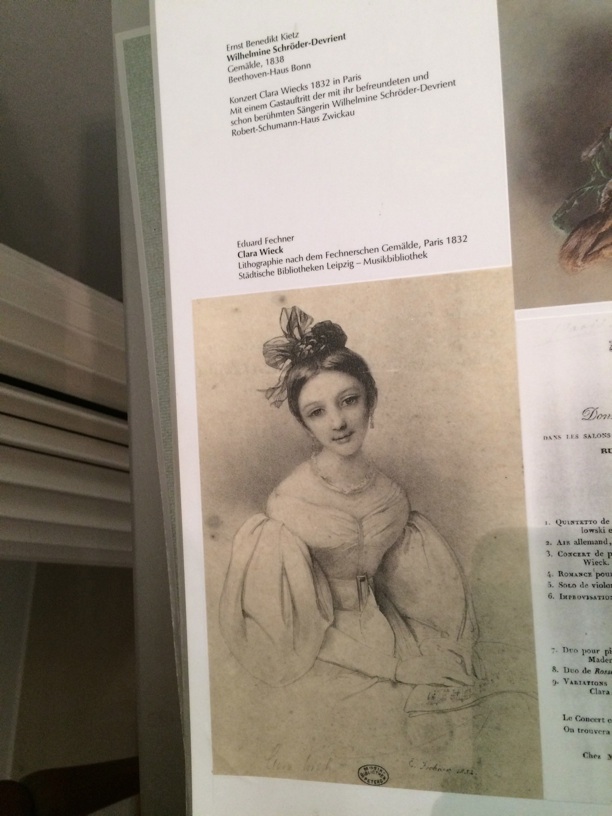

Clara Wieck around the time Robert first met her

Schumann 4th Symphony manuscript page

opening page from Schumann Piano Concerto

Portraits of Clara and Robert, with Mendelssohn below

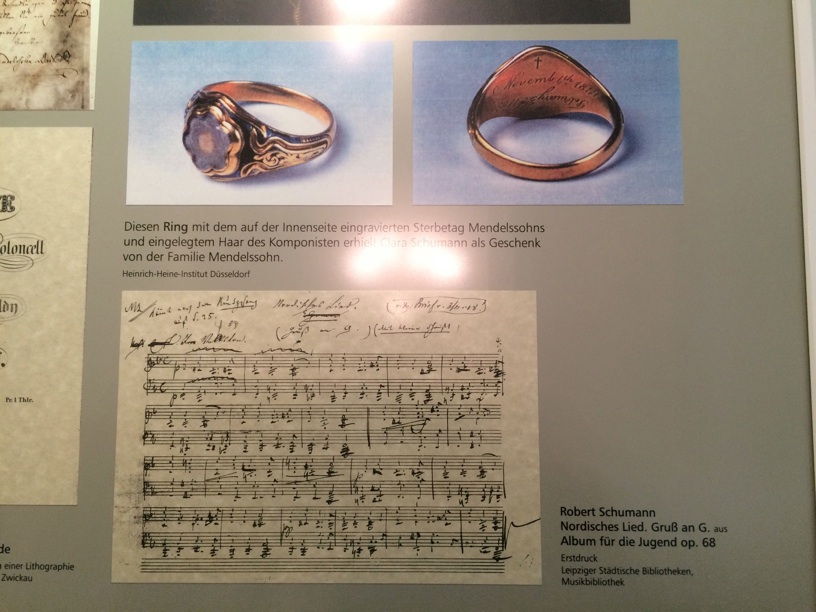

Ring given to Clara with a lock of Mendelssohn's hair!; below, manuscript from Robert's piano piece Nordisches Lied from Album for the Young

The museum has a beautiful piano you can play that was built in 1860 by Clara’s uncle, Wilhelm Wieck, a student of the famous piano builder Julius Blüthner. I can tell you that Schumann’s Arabesque sounds perfect on it :)

Wilhelm Wieck piano 1860—very beautiful and intimate sound, perfect for Schumann and Brahms intermezzi!

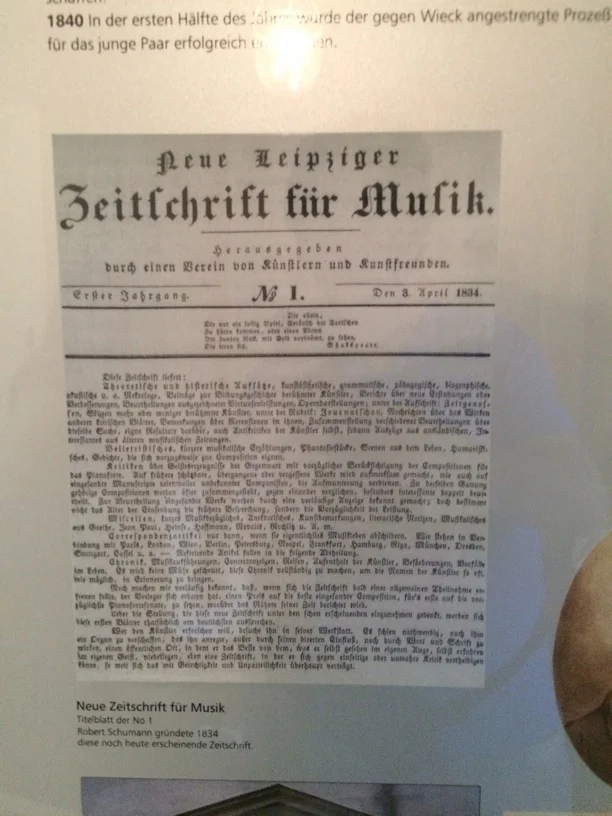

Concerts are given in the hall during the year. Another room has Schumann’s study with copies of his Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, the periodical he founded and for which he wrote such superb music criticism, introducing readers to Chopin, Brahms, and many other composers.

Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Schumann's famous music periodical

There are several manuscript examples, including the piano concerto and the first symphony, several portraits, and pictures of his writing desk (not from this house). But my general impression is that this museum is a random collection of Schumann memorabilia without any clear thread or context. It’s a fairly new museum, so perhaps it will improve with time.

Mendelssohn House in Leipzig

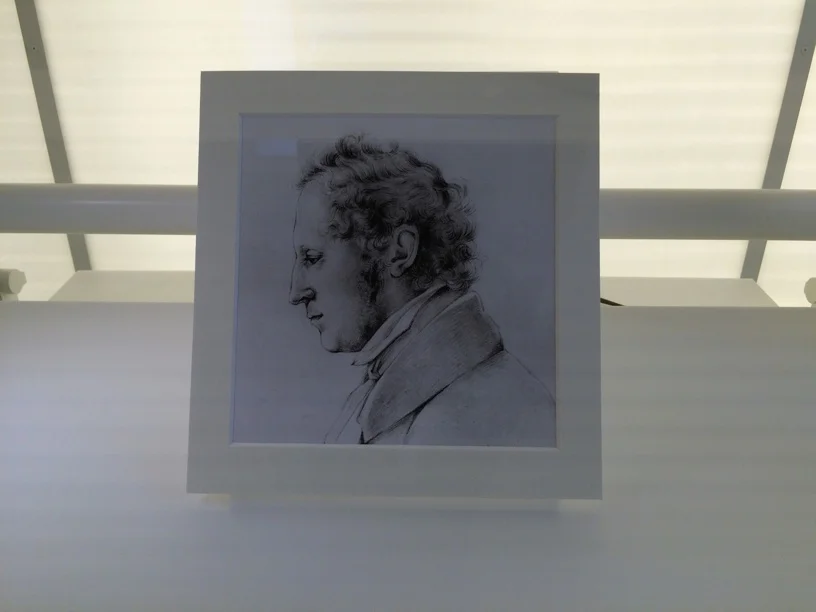

Portrait of Felix Mendelssohn

The Mendelssohn house in Leipzig is personal and revealing in a deeper way than other composer sites I visited. Mendelssohn House leaves you feeling as if you spent the day with Felix and some of his impressive friends. But it’s almost as if you are invited to be on a first name basis. No dominating atmosphere here. Mendelssohn’s home feels inviting and comfortable, even joyful. His study has been carefully reconstructed according to a watercolor made by the son of his teacher and friend, Ignaz Moscheles. We see a beautiful mahogany desk with shelves for books. Behind it, right at the window, is a high desk (for writing while standing?). Behind are bookshelves and two busts—one of Goethe and one of Bach. On the wall behind his desk are Mendelssohn’s beautiful watercolors, and next to the desk closest to the door is a console piano—all the coziness of a music professor’s study!

Mendelssohn's study reconstructed from a sketch by Felix Moscheles

The hallway wall is filled with portraits of Mendelssohn’s teachers and friends —Carl Zelter who introduced Felix to Bach, mentor and friend Johann Goethe, a young violinist Mendelssohn promoted, Joseph Joachim, his friends Clara and Robert Schumann, Chopin, Cherubini, Jenny Lind, etc. Clearly he was a social animal.

Hallway portraits of Mendelssohn's teachers and friends

Key to the names of each portrait, a "who's who" of 19th century musicians and writers

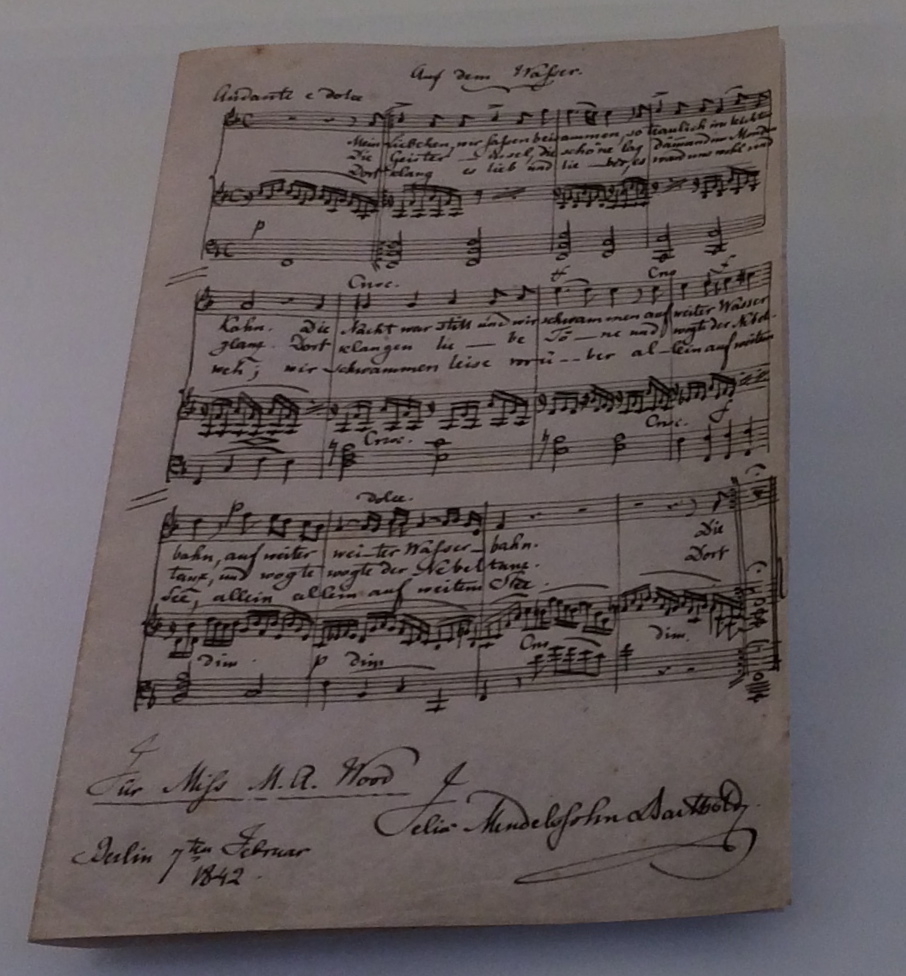

His music sketches and manuscript are just gorgeous. He clearly spent time perfecting a complex and ornate signature that is just beautiful. On display is a brief musical canon he sketched in London in 1844. The clue is that the scripted “F” in “Felix” arcs all the way up to where the second voice should enter.

An entire song for voice and piano, Auf dem Waßer, is set on a page dated 1842 in Berlin.

But where are examples of his chamber music? Dvorak and Mendelssohn’s chamber music form the core for every chamber festival on the earth. Why don’t museums have examples of at least some trios or quartets?

Back to the displays. We see a cast of Mendelssohn’s hand and his rastrum—a pen with a tiny rake end used to draw music staff lines (anyone know where I could get one?).

Mendelssohn hand cast and rastrum (foreground) used to create music staves

We read about Mendelssohn’s enormous impact on the Gewandhaus orchestra. He expanded the orchestra from double to triple winds and added many more strings. Mendelssohn essentially invented the “theme” programming that remains popular today with orchestras. For instance, he would create a series of concerts devoted to specific musical periods—Baroque, Classic-era, etc. Audiences were delighted with this new approach and subscriptions increased to the point that the directors renovated the concert hall during Mendelssohn’s tenure, adding an additional 200 seats. Mendelssohn also lobbied hard and successfully on behalf of the musicians to increase their salaries.

As if composing, conducting, and performing were not enough, Mendelssohn also created the oldest music school still in existence—the Leipzig Conservatory. The musicians of the Gewandhaus orchestra became the school’s first teachers, as well as Mendelssohn’s friends (Robert and Clara Schumann both taught there for awhile). Has any other composer given more to music? We also can’t forget that Mendelssohn began the Bach “mania” that continues to this day with his performance of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. In honor of Mendelssohn’s Bach revival, the new St. Thomas Church interior devotes one entire stained glass window to Mendelssohn.

Speaking of visual art, an entire room in the Mendelssohn House displays his watercolors. His eye for detail, proportion, and color is just extraordinary. He especially sketched and painted places he traveled, sometimes creating the most beautiful postcards. I couldn’t help but realize how his sketches of landscapes probably cemented them in his mind in a depth we today who snap photos just can’t possibly imagine. So much talent—had visual art been his calling, one can only wonder where his ability would have led.

Mendelssohn exquisite watercolor of Thun, Switzerland

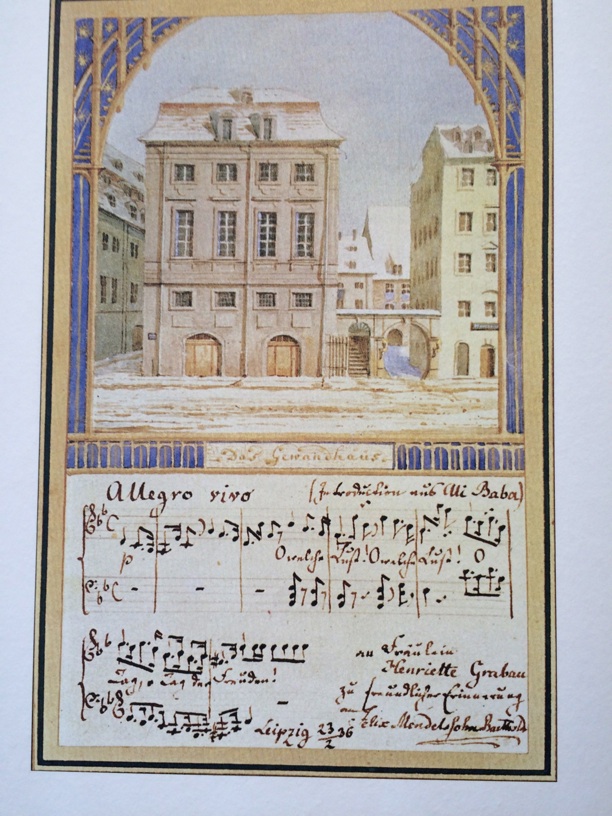

Imagine receiving this incredible original artwork and manuscript postcard of the Gewandhaus in the mail from your friend Felix Mendelssohn!

With all he achieved, how is it possible Mendelssohn only lived to be 38? He died world famous and deeply venerated. But in the decades after his death, his reputation declined. In the museum display, three reasons were given: 1) people felt Mendelssohn came from a privileged life and had not suffered like a “true” artist, 2) only his most popular works continued to be performed, and were often done in poor arrangements, and 3) oh yeah, growing anti-semitism in Europe. Just three years after Mendelssohn died, Wagner wrote his terrifying anti-semitic essay Judaism in Musik aimed dead center at destroying Mendelssohn’s legacy. Mendelssohn was a real problem for Wagner, because while it was easy to toss off other Jewish composers as inferior “imitators” of the Bach-Haydn-Mozart-Beethoven tradition, it took a major reality distortion to assert that Mendelssohn’s musical genius was not equal to it.

Finally in 1892, a large monument to Mendelssohn was erected in front of the Gewandhaus. And here was the part of the museum that had me in tears—two separate letters. In 1936, his monument was removed in the night and destroyed. The first letter was from Mendelssohn’s grandson to the mayor of Leipzig asking the reason for the removal of his grandfather’s monument. The second letter was the Mayor’s response and it is chilling:

“Previous generations did not succeed in erecting a monument to the greatest musician and writer of this city, Richard Wagner, whom I am pleased to report was also a vehement anti-Semite. And yet a monument was erected to a Jew at no less than the prime location in front of the famous Gewandhaus…The question of whether Mendelssohn achieved anything is totally irrelevant. He was a Jew, and as such cannot represent a German city renowned for its music.”

(letter from Mayor Rudolf Haake to Dr. Felix Wach February 5, 1937)

Translation on display at the Mendelssohn House of the Mayor of Leipzig's letter of response to Mendelssohn's grandson regarding the removal of the Mendelssohn monument in 1936.

That was 1937. Mendelssohn’s reputation since WWII soared and no one today questions his importance in Leipzig or his importance in the German classical music tradition. Yet during the time I was traveling on this composer “pilgrimage” in summer 2015, the Berlin Philharmonic appointed a new music director, Kirill Petrenko, who happens to be a Russian Jew. A German media outlet (NDR) described Petrenko as a “tiny gnome, the Jewish caricature.”

Jewish Conductor Petrenko Greeted with Anti-Semitism in Germany Appointment

Universal outcry forced a quick retraction in Germany. But nevertheless, the feeling from 1937 clearly persists.

I mentioned that when visiting the composer homes, one feels contemporary with the times they lived. I hadn’t expected that feeling to extend to this dimension as well. So much beauty. So much darkness. Go visit Mendelssohn House.

In Part 3, we finally get to J.S. Bach. I will relate my experiences hearing Bach’s music in a religious service at St. Thomas Kirche and visiting the Bach Museum across the street—hands down the most comprehensive and illuminating composer museum you could imagine..

_________________________________________